Lent is that time in the Church calendar historically set aside for an “under the hood” diagnostic of those things most needful for the optimization of our lives in Christ. It is a rich time, not for mere maintenance, but for the introspective dialogue with one’s own inner voice that, in concert with God’s voice, guides us to “practice resurrection” as Wendell Berry so eloquently advises.

Allow me to clarify with a story.

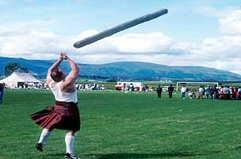

I’ll never forget the day I first told my bewildered parents that I wanted to learn how to play the bagpipes. I was seven. I had just watched a televised Edinburgh Military Tattoo replete with color-laden, swinging kilts, swashbuckling pipers, and swishing notes all clammering for attention under the bright lights of a night-lit Edinburgh Castle. From the first humming drone and pinched gracenote to the final cannon blast salute I was forever hooked. A seed was planted that has matured into a forty year career of performing, accompanying, competing, composing, judging and recording with this enigmatic instrument.

Under most circumstances, when one’s child shows even the slightest interest in music, it is generally accompanied by proud winks of acknowledgement, cackled whispers of “I always knew he had it in him” and blustery coffee room comments like “it was only a matter of time” or “our family has always been musical.”

At the risk of understatement, this was different.

Any parent hopes their groomed and dapper ten year old will be playing Chopin on the piano in the mall with the other bright and shining stars. With this announcement, those hopes were dashed. Instead, my parents (and poor, unsuspecting neighbors) would be forced to endure the long, loudly awkward learning curve the instrument promises all student comers. It most likely involved having to apologize to neighbors only pretending to be patient as some overly confident ten year old insists on playing, poorly, in the backyard.

On Sunday…night…late.

They did all this with patience and pride.

Similarly, a doting, jealous God waits like a holy panther ready to pounce on any sign of our awakening to God’s romances kissed in our direction. Patient and crouched, hopeful and proud, our Holy Parent, yearns for all that is best in our human lives. From first light of spiritual birth to the brighter light of eternity in us, God waits to discover, or uncover, our intentions toward God.

What does this mean? Will he stick with it only long enough to tire of it and move onto something else, despite the considerable expenditures of cash and time? Or will he seek to express a complex nature through an equally complex instrument designated for oatmeal-savage mystics whose love for center stage is well serviced here?

To parents, it simply does not matter.

For a bagpipe to function optimally it must have at least three things. It must be utterly airtight, with no chance whatsoever for the not-so-easily-blown instrument to lose any of its chief operating component, air. The only allowable air should be that in service to the four reeds dependent upon a steady stream of the same, and all at a highly regulated psi. Likewise, the best Lenten practices lend themselves to tightening up any holes in our spiritual lives, perceived or not. We must place ourselves willingly at the behest of a God who tugs at the cords holding our varied parts together in order to ensure the least “leakage” of the precious commodities of abundance and hope. In so doing, we relinquish our ownership over all we think to be primary for the singular goal of obtaining God alone. A heartily resonant helping of “lov[ing] the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength” will do nicely here.

Secondly, it must possess the best reeds available (4 in all) in order for all energy expended to be done in service of a quality sound. It will only be as good as the weakest link in the complex chain of piping accoutrements. An unfortunate side effect of sin is our willingness to settle for counterfeit grace, for the short-term fix we think will provide quick, spiritual benefit but which, in the end, only multiplies our sorrows. All that we strive to do, at whatever level and for whatever reason in our pursuit of God will ultimately lead us astray unless we see it as pure grace; as gift. God’s purposes in us will always guide us to “whatever is true, whatever is honourable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is pleasing, whatever is commendable…any excellence and…anything worthy of praise” (Phil. 4:8).

Finally, all of its constituent parts of wood, bag and reeds are to be kept as impervious to excess moisture as possible – moisture that can foul the best reeds and, in worst-case scenarios, shut them down entirely. As with most mouth-blown instruments, outside influences of weather, barometric pressure, humidity and temperature have profound impact on whatever sounds are forthcoming. The via negativa of the spiritual life is to renounce anything that adversely affects one’s progress in the Way. John Calvin believed that self-denial lay at the heart of all spiritual transformation. To the degree we keep ourselves impervious, or at least well resourced, against the worst that life will most certainly throw at us, we will remain progressively more immune to outside influences that cause cracks to appear in our deepest parts where we need it to be well-contained and whole. The sage in Proverbs encourages us to “keep [our] heart with all vigilance, for from it flow the springs of life.”

It is a standard faux pas of pipers to assume that the biggest, fattest reeds will automatically proffer the biggest, fattest sound – an important and coveted feature of the instrument. At issue here is the fact that, the bigger the reed, the bigger the effort required in playing it.

The dilemma is one of physics. Sometimes trying harder with bigger than normal reeds simply forces a law of diminishing returns. In the young piper, less familiar with those physics and more inclined to early onset frustration with an already mystifying instrument, this can be daunting to say the least. As one grows in knowledge of bagpipe physics it becomes apparent that the best sound production isn’t merely one of effort. It is primarily one of the integrated and streamlined functioning of all the factors necessary to make the instrument the beautiful experience, and sound, it can be.

Similarly, the spiritual life, like the Highland Bagpipe, works optimally when we can see the big picture; how each element fits into the whole and, as a result, produces what we will ultimately become. God’s intentions in us include all elements of our existence, our choices, our conversations, relationships, experiences both good and bad, love gained and lost, anger welcomed and spurned, pain suffered and healed…everything.

The seasoned piper learns that a tightly-fitted, well-maintained, thoughtfully set up instrument makes for the best possible sound. Then, what at first can be a most, let’s say…unfortunate, sound ultimately becomes something of beauty that actually produces a bigger sound with greater resonance, nicer pitch and less energy. Good discernment and skill leads to something leaner that is, in turn, louder but also sweeter to the ear.

This is the magic of the Lenten gift of grace. We are better poised to usher a generally gangly, uncomfortable instrument into places of sweetness, strength and otherworldliness. That is how a bagpipe should sound. That is how I’ve heard it sound.

I think you know what I mean.