Much has been written about this period of the holy story the church has called Christmastide. We hear words like waiting, longing, anticipation, inbreaking, birthing, hoping, emmanuel, and sing of shepherds and sheep, angels, alleluias and announcements, mangers and mangy stables and , all in voices bright sing gloria in excelsis deo (glory to God in the highest).

Consumer culture rides its coattails toward a bloated bottom line. Corporate culture plays with its nuances to encourage warmth of feeling and brand vibes. Christian culture uses it to battle their annual “war on Christmas.” Cancel culture uses it to remedy the former. And, Hallmark culture uses it to sell Thomas Kinkade paintings (I have nothing against him, I promise!). Such a tangle of ideas and emotions, all running rampant…at Christmas.

Even in an arguably post-Christian culture, it is challenging to share anything particularly new about a story this well known. For those of us tasked with its telling it can be especially difficult to reverse the potential for a familiarity-bred contempt, both in the church, and in the culture at large. But tell it we do. Every year.

The stultifying caprice of our COVIDays, coupled with unparalleled political farcity seems to have diminished our ability to see any hopeful horizons and consequently, ravage our capacity to dream. One wonders if one can ever again, wonder. As the writer of Proverbs once observed, “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but a longing fulfilled is a tree of life” (13:12).

But, dare we think ourselves alone to be the hope-starved? Those to whom the heavenly babe first came were far more so.

Read appropriately, in its original context, the birth narrative of Jesus would have sounded incredulous. A questionable yarn akin to UFO talkies or gu’rmint conspiracy theories in the local version of Bethlehem’s National Enquirer. ‘Twould have been anything but a family-friendly, consumer-ready tale fit for animated movie screens and glittering holiday bling.

Instead, the Hebrew nation fixated on their lot as Roman-branded religious fanatics and kicked against the goads of military occupation. And, theirs was an occupation not just politically by the Romans, but theologically and morally by religious leaders pretending to follow Torah but largely interested in political safety and the biggest voice at the table (sound familiar?).

Long had they given up hope that anything would actually change. That their station might somehow improve. That, in great, great grandpa’s memory was something about messiah, the line of David, and covenant promises, among other fantastical things. They had done what almost every other conquered people has always done – settled into the long night of mediocrity and acceptance. Their survival mode button was stuck in the ‘on’ position.

Oh, there were outliers for sure. History is replete with them. There are always a remnant of stalwarts who refuse such resigned demeanour.

For example, Anna, whose long and lonely life had been given to prayerfulness and presence. Simeon, similarly, happy just to die having seen the fulfillment of a promise. Zechariah, whose priestly advocacy over Israel was well-known and whose doubts equalled his dedication. Elizabeth was giddy just to be pregnant in old age (God rather fancies such stunts), let alone with the New Testament’s resident off-the-grid hippy. And, of course, Mary. Aw, Mary – sweet but strong, young but wise, believing but thoughtful. Mary, perhaps more than anyone, understood the full importance and impact of what was told her by the angelic messenger. Apparently yes, she did know. ; )

“My mind is blown and my heart is full. Okay, so if I’m hearing you correctly, God’s finally doing something? Not just anything, but making the cosmic statement that the lesser is the more, the small leads the great, the poor rule over the rich. It’s all been upended, and you remembered everything that you’ve ever promised to me and my people? I’m in!”*

It is on the one hand a strength that such a story resides deep in our shared memory and finds revered place in our common consciousness. But, sometimes the familiarity of character, plot, and setting can sublimate the luminous mysteries at work under the surface. We kinda know the story but it doesn’t move us anymore. The aha! has been lost in the constant retelling that lacks reliving.

We can attribute much that is warm and good and beautiful to our affixation with the Christmas story. We still value the notion, however vague, that love lies at its heart, that forgiveness has at least something to do with all this, that family and community somehow matter, and that God doesn’t mind getting his hands (and diapered backside) dirty.

In our cynical moments, if nothing else, it keeps us looking for good deals at Walmart and happily arguing over Starbucks cups. And who doesn’t love that after fighting winter traffic for two hours?

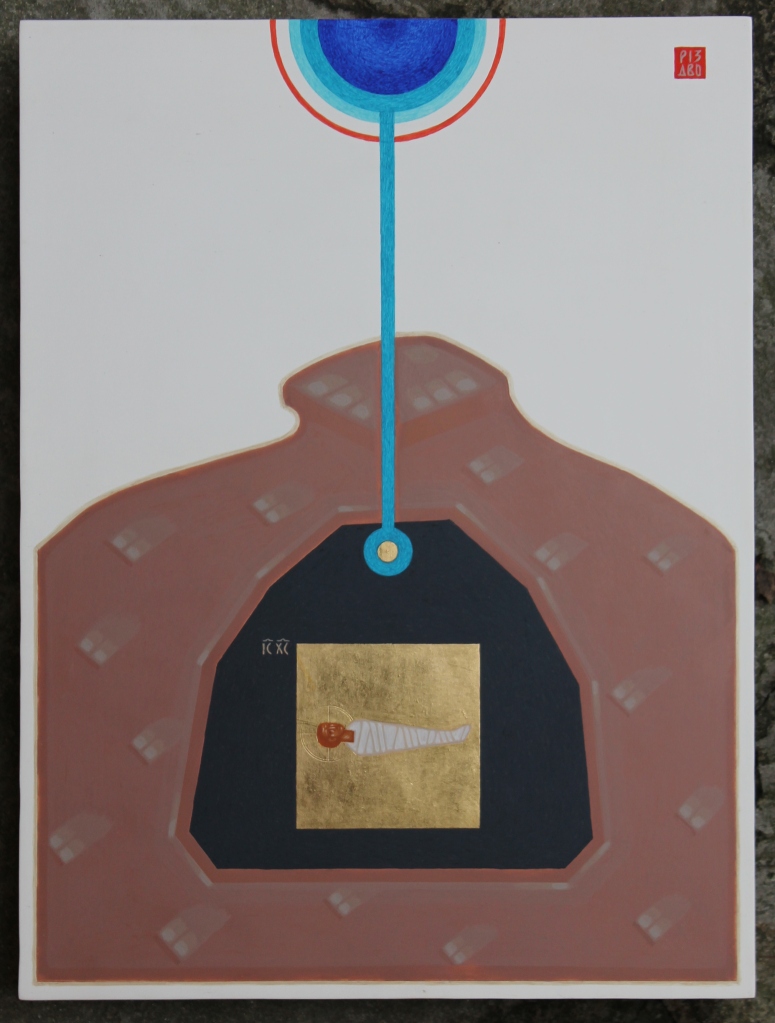

But, upon reflection, guided by the Spirit who guided the star who guided the wise men who guides us still, we confess Christmastide to be a picture of heavenly surprise. To retell such a treasured tale should be of all things, an exercise in practicing surprise.

And everyone loves surprises.

A happy and surprising Christmastide to each and every one of you!

*Rob’s take on Luke 1:46-55, often called “The Magnificat” or simply “Mary’s Song of Praise.”